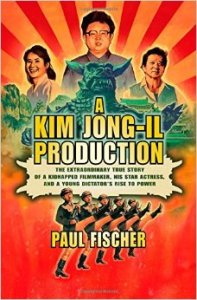

After such incredible coverage for his book “A Kim Jong-Il Production” it’s an absolute pleasure to have author Paul Fischer give his time to a Q&A for this rather niche blog. Giving further insight into what is the most remarkable story associated with North Korean cinema, I advise all those with even a passing interest in North Korean, cinema or humanity to hunt down a copy of his book.

As mentioned in the last post about the This American Life podcast, the story… well, why don’t we let the blurb explain the story:

Before becoming the world’s most notorious dictator, Kim Jong-Il ran North Korea’s Ministry for Propaganda and its film studios. Conceiving every movie made, he acted as producer and screenwriter. Despite this control, he was underwhelmed by the available talent and took drastic steps, ordering the kidnapping of Choi Eun-Hee (Madam Choi)—South Korea’s most famous actress—and her ex-husband Shin Sang-Ok, the country’s most famous filmmaker.

So let’s get on with the Q&A…

How did you first hear about the incredible story of the North Korean dictator who kidnapped a director and star and forced them to make films?

I remember reading about it in passing in the odd newspaper article when Kim Jong-Il was still alive. Never more than “Kim is such a film fanatic it is said he owns the largest private film collection in the world, and is rumoured to have once kidnapped his favourite director to ask him to make films for him” – that kind of thing. Always short and never quite accurate. I loved the idea as a basic concept for a fiction work, and filed it away to play with later.

And then one day in the pub for some reason or another I mentioned this idea to my girlfriend, and she asked me what exactly had happened. Since I didn’t know I started looking up details on my phone and immediately became obsessed with it. Realising who Shin Sang-Ok and Choi Eun-Hee were, seeing my first pictures of Kim Jong-Il as a dapper young film producer, understanding how film and entertainment played a part in inventing the modern theatre state… it was just an amazing story. And I knew right away it was a book.

Shin’s lifestory is so remarkable – with periods of film-making spread over South Korea, Hong Kong, the DPRK and the US – how did you know which aspects of his life to concentrate on?

Shin’s lifestory is so remarkable – with periods of film-making spread over South Korea, Hong Kong, the DPRK and the US – how did you know which aspects of his life to concentrate on?

That was one of the main challenges. It’s true of Choi too – before the kidnapping, she’d run away from home as a teenager, married an abusive husband, been enlisted by the North Koreans in the Korean War, escaped, got enlisted by the South Koreans, been raped, earned a divorce from her abusive husband, become the most famous and best paid actress and model in South Korea, directed films, married Shin, divorced Shin because he had a secret second family… There’s just a ton there. And then the historical context. And Kim Jong-Il’s own background. And so on.

The basic rule I had was that the book was about the kidnapping. That that would be the through line, and that anything not absolutely necessary to understanding that story would have to be cut. It was easier said than done though. I was so fascinated by all the layers that the first part of the book, the lead up to the kidnapping, was huge for a long time. My editors in the US and UK were fantastic at helping me shape it and cut it down and make it part of the narrative rather than endless pages of exposition.

After exploring the films that Choi and Shin made, were you ever worried that the colourful story would detract from the impressive films the two made?

I didn’t, actually. I think it helps. We had a screening in New York recently of “The Houseguest and My Mother” (1961). The audience came because of the book, and then discovered this great, funny film. People have tweeted me that the book makes them want to watch some of Shin’s films and asking where they should start. It’s great because I was always keen that I wanted the book to be about Shin and Choi. Kim Jong-Il’s not the meal, he’s the bait.

I didn’t, actually. I think it helps. We had a screening in New York recently of “The Houseguest and My Mother” (1961). The audience came because of the book, and then discovered this great, funny film. People have tweeted me that the book makes them want to watch some of Shin’s films and asking where they should start. It’s great because I was always keen that I wanted the book to be about Shin and Choi. Kim Jong-Il’s not the meal, he’s the bait.

What impact do you think Shin and Choi had on the North Korean film industry? Was it a lasting impact?

It didn’t last I don’t think, no. It feels to me that after they escaped, Kim Jong-Il felt burned, and as he grew older and more paranoid the films he oversaw went back to being safer, staler propaganda. And then the Sino-Korean border got more porous and foreign films got smuggled in and it became clear Kim’s films couldn’t compete and that put a nail in the coffin of that national industry a bit, which still turns out a few films and makes documentaries and newsreels and the occasional headline-grabbing co-production, but as an industry is really kind of dead.

I do genuinely feel the three years Shin worked in North Korea were the best years of that industry. He had a sophistication and a versatility, and those were two things North Korean cinema isn’t exactly famous for.

Do you think any of the movies Shin made during this period had artistic merit?

I like “Salt” (1985) a lot and I think it does. “Hong Kil Dong” (1986) – which it’s unclear whether Shin directed or just produced – is great fun. And of course there’s “Pulgasari” (1985) which I enjoy on an Ed Wood kind of level but which many people believe to actually be a masterpiece of subtextual subversion, a kind of protest film in the guise of a kaiju car crash. Shin never let himself be drawn out on that point, but if that theory is true – which it could be, although it sounds far-fetched to me – then “Pulgasari” (1985) becomes a fascinating artist work, a multi-layered commentary on working under duress.

What were the most surprising things you discovered? Was there anything you wish you’d found out the answer to?

Yeah, plenty. I wish I’d been able to find a picture of Woo In-Hee. I wish I’d found the people involved in the actual physical part of the kidnapping – the colleagues of Shin’s who betrayed him. I wish I’d met Shin before he died. But they’re sort of anecdotal things and happen with every project. As for surprises, the whole thing was a surprise to me. It was fantastic fun to write. North Korea as a theatre state, as a performance, and how that was created, scripted, and enforced, that’s been endlessly captivating to me.

Once you’d brought together all your research and written the book, what was your opinion of Shin as a person?

You become very attached to the people you write about so I’m naturally very fond of Shin. And of course he’s taken an even bigger place in my mind because I never met him, he’s elusive. I met Choi Eun-Hee and we became friends, she’s a person I know. Shin is an image in my mind.

In the research, the writing, the interviews, the testimonies (his and those of others), I found a showman, a hustler who was obsessed with the cinema, obsessed with his own work, ambitious, full of bluster and drive but also insecure about whether he was an artist or an entertainer or a businessman or all three. He seems full of contradictions. He never wanted to be perceived to have failed at something but also didn’t seem to give a damn if people judged or disagreed with him. He claimed to be a conservative traditionalist but in practice was anything but. He was a romantic – who slept around and had a secret family. He mentored and looked after people who adored him his whole life, but he could also be incredibly cold and detached, as when he put his career before his own family or lovers. He kept his cards very close to his chest. Incredibly talented, incredibly hard-working, incredibly resourceful. And somehow – from what I gather – matured and grew more compassionate, less self centred, through the experiences in North Korea. He feels to me like one of those great movie showman characters – like Orson Welles or Cecil B. de Mille or Darryl Zanuck. He was a fascinating puzzle.

Do you find watching DPRK films remotely enjoyable (people always ask me this)?

Hahaha. I do but I “blame” the book. I don’t think I would have watched a North Korean film straight through to the end in my entire life if it hadn’t been for this. Now I really enjoy them because I see a whole country, a whole culture, a whole world reflected in them and how they present themselves.

And finally, was Shin really kidnapped? [Note: There’s often been the suggestion that Shin faked the kidnapping so that he could defect to the DPRK]

I am convinced he was. There’s an afterward in the book that goes into the evidence as I found it and the investigative process I went through and to me it seems overwhelmingly to show he and Choi were kidnapped. There are logic holes the size of the USS Pueblo in the voluntary defection theory. I think the simple way of putting it is, imagine a criminal court case in which the accused has a proven history of the exact same crime, in which the victims testify consistently over time, in which associates of the accused confirm the victims’ testimony, in which there are photographs and audio recordings, authenticated by state experts, backing up the victims’ testimony, and a prosecution timeline that the defence cannot refute. That sounds like a pretty clear-cut case — and the kidnapping story has all of those cornerstones backing it up.